Fury Read online

PRAISE FOR

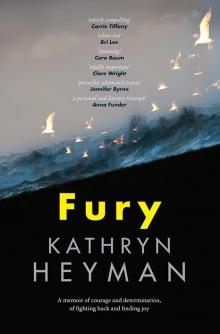

Fury

‘This sensitive, searching book broke my heart. Heyman transcends her harrowing Australian girlhood by taking herself to sea. That she regains her body and her self is a triumph. Utterly compelling.’

Carrie Tiffany, Stella Prize-winning author of

Mateship with Birds

‘Kathryn Heyman’s Fury is a masterful work, a personal and literary triumph. Heyman has every kind of courage there is. As a girl she dares the world to treat her as equal. It doesn’t, but she holds on to her ambition and her imagination in the face of the thousand shocks that female flesh is heir to; the litany of sexual terror women and girls dodge each day.

‘Fury is a coming of age story for our times: a girl faces a violent sea and patriarchy in a battle for body and soul. Its story is breathtaking. Its cumulative ambition, story by story shows the making of a writer capable of this magnificent work, at the same time as putting the locus of shame for sexual violence in patriarchy back where it belongs—with the perpetrators. And so, Fury is searing, thrilling and redemptive. This book is a demonstration of how courage and fury and words can save you. They can make you the heroine of your own story.’

Anna Funder, Miles Franklin Prize-winning author of

All That I Am

‘Raw and bloody and real. The hundreds of indignities and offences accumulated over a lifetime of class and gender warfare boiled down into one white-hot book. Heyman’s skill keeps this angry book from shouting or devolving into didactics—it’s the written equivalent of when you’re so mad you don’t even raise your voice. Heyman is a woman looking at the past with clarity and speaking to the present clearly: enough.’

Bri Lee, author of

Eggshell Skull and Beauty

‘In Fury, Kathryn Heyman trawls through the treacherous waters of emergent womanhood with the keen eye of the hunter and the broken heart of the hunted. Her story of sexual abuse is at once foreign—adventure on the high seas!—and infuriatingly familiar, as exotic as a Red Emperor, as common as a goldfish. I read this book in one jaw-clenching, gut-wrenching, fist-pumping sitting. Distressing, thrilling, immaculate—and vitally important.’

Clare Wright, Stella Prize-winning author of

The Forgotten Rebels of Eureka

‘Fury is a gripping and brilliantly written story of a young woman’s survival, up there with the very best of adventure memoirs such as The Salt Path by Raynor Winn or Cheryl Strayed’s Wild. Kathryn Heyman has pulled off an amazing feat, giving a true story of trauma and recovery all the narrative pull and beauty of the best of novels. Her account of the tough realities of life for an unprotected young woman, of the over-riding imperatives of education and class, is a literary work that will stand the test of time and has international bestseller written all over it.’

Louise Doughty, author of Apple Tree Yard

‘Kathryn Heyman’s Fury is a raw, unflinching memoir about surviving the relentless assault of growing up female in this world, coupled with an extraordinary story of adventure of a young woman working on a trawler in the Gulf of Carpentaria. Moving and ultimately triumphant, it’s story of survival and reinvention about a woman who refuses to let the system, her family and the men from her past, destroy her will to live and the truth of who she really is. It’s the kind of story I needed to read right now. Inspiring and brave.’

Sarah Lambert, screenwriter Lambs of God,

and producer and screenwriter Love Child

‘This book is important—a vital addition to the national conversation. A searing, moving, deeply honest achievement.’

Nikki Gemmell, author and commentator

‘I can’t remember when a book gripped me so tight and so hard. This stunning, harrowing memoir is a fierce testament to the power of words and books to save a life. It is no exaggeration to say that reading rescues Heyman from poverty, abuse, violence and danger on the high seas, offering her a chance to remake herself in a defiant act of courage and will. The result is an intoxicatingly triumphant story that defies the odds, as a fearless young woman’s spirit refuses to be crushed by the law or defeated by a roiling sea.’

Caroline Baum, author of Only

‘Fury is that old, old story in which a vulnerable girl becomes a victim, but it is made new by Kathryn Heyman’s bold, brave and poetic voice. She tears open what it means to exist in a predatory male world. It’s a confronting and compelling memoir, and also an uplifting one: the great triumph is in the art, the storytelling, the very words, that have saved her.’

Debra Adelaide, author of Zebra

‘This powerful, ultimately joyous memoir shows how—in the teeth of a gale—a damaged girl can find her own strength, and fight for her own path.’

Jennifer Byrne, journalist and broadcaster

‘This book grabs you by the throat from the very first sentence. Each chapter is like a punch in the guts. It will move you, shock you and—yes—make you furious.’

Jane Caro, author of Accidental Feminists

‘Fury took my breath away. Heyman writes with such brio, muscularity and physicality; her trademark humour, honesty and energy vibrate on every page. Her work is like no one else’s—however, for the breadth, scope, lyricism, originality and power of the writing, for the way it captures a vernacular voice and for the sensibility, an honest try might be Sylvia Plath crossed with Kerouac and Peter Carey. This memoir is a triumph, the journey it tells of a girl shaping herself in her own fashion a salutary reminder of the crushing oppression that girls face every day and the courage—and the fury—that it takes to get out from under that.’

Jill Dawson, author of The Language of Birds

Kathryn Heyman is a novelist, essayist and scriptwriter. Her sixth novel, Storm and Grace, was published to critical acclaim in 2017. Her first novel, The Breaking, was shortlisted for the Stakis Prize for the Scottish Writer of the Year and longlisted for the Orange Prize. Other awards include an Arts Council of England Writers Award, the Wingate Scholarship, the Southern Arts Award, and nominations for the Edinburgh Fringe Critics’ Awards, the Kibble Prize, and the West Australian Premier’s Book Awards, as well as the Copyright Agency Author Fellowship for Fury.

Kathryn Heyman’s several plays for BBC radio include Far Country and Moonlite’s Boy, inspired by the life of bushranger Captain Moonlite. Two of her novels have been adapted for BBC radio: Keep Your Hands on the Wheel as a play and Captain Starlight’s Apprentice as a five-part dramatic serial.

Heyman has held several writing fellowships, including the Scottish Arts Council Writing Fellowship at the University of Glasgow, and a Royal Literary Fund Writing Fellowship at Westminster College, Oxford. She taught creative writing for the University of Oxford and is now Conjoint Professor in Humanities at the University of Newcastle. In 2012, she founded the Australian Writers Mentoring Program.

www.kathrynheyman.com

www.writermentors.com

ALSO BY KATHRYN HEYMAN

The Breaking

Keep Your Hands on the Wheel

The Accomplice

Captain Starlight’s Apprentice

Floodline

Storm and Grace

This memoir is a literary work. To protect the privacy of people who did not ask to be written about, some names and identifying details have been changed or re-attributed.

First published in 2021

Copyright © Kathryn Heyman 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the g

reater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76052 937 6

eISBN 978 1 76087 459 9

Set by Bookhouse, Sydney

Cover design: Sandy Cull, www.sandycull.com

Cover images: Alamy Stock Photo

For Stephi Leach,

who saw the woman that the girl might become,

and helped me see her too

CONTENTS

COVER PAGE

PRAISE

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ALSO BY THE AUTHOR

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT PAGE

DEDICATION

CONTENTS

BEGIN READING

AUTHOR’S NOTE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Bloody Bonaparte. He shouted into the air, the words flapping away from him like seabirds. You fucker. This fucking gulf. His shouting turned to howling, the pitch running higher and higher. His face lifted to the storm-whipped sky, a fist raised to the wheeling seabirds, their clacking squeals drowning him out. I caught only occasional words: fucker, Bonaparte, useless. Some words flew out to me, teetering on the metal trawling boom, the rust sliding into my palms, the storm spray spitting up. The deck seemed an ocean away, never still. Even with the rolling of the boom, I could feel the constant tremor in my legs. I was fifty metres from the safety of the deck, standing on a piece of metal less than a foot wide. Twenty metres below me the dark ocean rose and fell, surging with its foamy mouth.

Rust, the taste of it, mixed with salt, with fear. Forever after this, I will associate the smell of rust with fear, with the arse-clenching terror of almost-certain death. Despite all the moments that led me to that trawling boom, and that storm in the middle of the Timor Sea—all the moments of near-death, near annihilation—this is the one that turns my stomach to liquid years, decades, later. Even now, writing this on solid ground, my legs have begun to tremble. My body, asking me not to remember. We have got this far, my body and me, without trawling up the mud and mess of it all, the memories that made me.

On the deck, next to the gob-spitting, fuck-shouting skipper, the deckhand—Davey—held a light above his head. Each time another wave roared up, the light was swallowed by the water and the dark. Behind each loss of light, he called, Sorry, I’m sorry. Sorry not just for the loss of light but for his wounded arm, bandaged to the shoulder, which meant that it was me out there on the slippery boom, trying to pass tools down to Karl, the first mate suspended from the broken boards with a spanner clenched between his teeth while the waves roared. We should have hauled the nets up when the storm started. We should have learned some skills, had a less desperate, more capable crew. We should have—he should have—listened to Karl. We should have battened down, settled down, gone to ground. All the should haves, useless when the thick salt spray is in your face, when the black night is whipped by wind and wild rain. Desperation made us keep going, lowering the nets when we could hear the rumble across the sea, could feel the lift of the wind, the waves whitening as the sky turned dark. Karl had looked up at the sky, sniffed the air, and called up to Mick in the wheelhouse, ‘We shouldn’t shoot away. It’s going to turn bad.’

Mick had clambered out, standing with legs wide on the tray, hands on his hips, eyes narrowed while he followed Karl’s gaze. His first skipper’s job, a favour from the uncle who owned the fleet. It made him anxious, unsure of his own footing. The nets dangled above us; Karl’s hand hovered on the winch. Karl waited, and then added, ‘It looks like it’ll be rough, skipper. What do you reckon?’ He might as well have been an alpha dog, a wolf, rolling over to show his belly. But it didn’t work. When Mick shook his head and said, ‘We can’t afford to miss a catch,’ Karl nodded and said okay. It was only after the skipper scrambled back to the wheelhouse that Karl said, ‘He doesn’t know anything about what it’s like out here. He couldn’t read the gulf if it was printed on a poster in front of his stupid face.’

The booms on the Ocean Thief stretched out on either side of the boat, wide arms forming a crucifix across the moving palette of the sea. On a good day, these trawling booms glinted with tropical heat. Inhabited by temporary colonies of seabirds—terns with punk hairstyles, gulls spreading their white wings, sometimes a sea hawk—on those days they had something soothing, domestic, about them. A marine Hills hoist, an aquatic, static windmill. But not that day. Not that night.

My bare feet curved, my toes gripping the narrow width of the bar holding me unsteadily as the boat lurched. Following Karl’s instructions, I’d hooked my arms over the narrow band that formed a sort of rail above the boom. Mouth dry, terror at the back of my throat, I leaned forwards, clutching a Dolphin torch in one hand, the beam rising and falling as the wooden boards below me slapped up and down with the slide of the ocean. Waves smacked against the boards with the force of a punch. The metal cut into the softness of my armpits. Framed by the black of the water snapping at his feet, Karl’s face flashed in and out of the light, his hand reaching up to mine.

The belt of tools at my waist dug into me, the handle of something—a spanner? a wrench?—stabbing into the flesh at my hip, a relief from the pressure of the thin rail across my belly. Karl shouted up at me, but the storm whipped his words away. Ack. Asser. Ick. Uck. It was all noise, a wash and a roar of noise: Karl’s snippets, half-words that disappeared into the storm; the punch-roar of the waves; Davey on deck calling sorrysorrysorry; the skipper behind him fist-shaking, shouting; the shriek of dolphins trailing the fishing boat; my own bloody heart, the thudding of it.

We had heard the first crack of thunder earlier, but we put the nets out anyway. We’d held to the deck as the six-berth fishing trawler slid up and down relentless waves, and, when the rain started pummelling us, huddled in the galley. It was the shrieking of the dolphins that called us back out on deck, pods of them trailing the boat, the strange squeal louder than the storm. Karl and I leaned out on the gunwale then, squinting into the rain until we could see. The boards that held the nets steady had broken. We couldn’t get the nets up without mending the boards. And if we couldn’t pull up, with unstable nets heaving in a thrashing sea, we were unbalanced, likely to be forced over, or under, to become one more weekend news story of boats lost in the Gulf.

Karl raised his face again as another wave hit. The screw. Iver. Need. Mash.

Folding myself in two, I leaned further down, a screwdriver dangling from my hand. Karl reached up, but not close enough. My foot lifted off the boom, while my arms gripped tighter. On the deck behind me, Davey shouted a warning. The boom lifted then fell and the boards smashed towards me. The torch dropped from my hand just as another wall of water surged, pounding into my face, my eyes, until I was blinded, only feeling the turn of metal beneath me. I grabbed at something near, while the wall of the world—dark, impenetrable—came closer. Terns screeched, counterpointing the shrieking of the dolphins and the rattling inside my skull, a bass reverberation. Karl’s voice sounded below me, a call, a warning, and then there was the clang of the chains and a sudden smack to my face. The thickness of blood then, and soundless dense black.

The party was in Sydney, in an apartment full of people I didn’t know. Drama students, mainly. Beautiful people, funny people, smart people. A friend, Penny, had dragged me along for reasons that I still can’t fathom. I do remember what I was wearing. I’ll always remember that, I suppose. Earlier that year I’d found, in a charity shop, a green-and-black-checked vinyl trench coat with a pointed collar and a neat belt. Inside the vinyl I sweated like the inside of a car, but it was worth it. I had a little skirt on und

erneath, and green pointed boots. Boiling, sweating, and the fattest girl in the room, I kept drinking. And I kept drinking, waiting for someone to notice me, to speak to me, to find me funny, or interesting, or to like my careful green trench, to notice how witty it was, how ironic. But none of these things happened.

Penny stayed in the kitchen, running her hand down the arm of someone called Jeff, who’d just landed a role in a new film about the heroes of the Kokoda Track. He had one line, and he kept repeating it in the kitchen, while Penny tilted her head back and laughed, revealing the long line of her throat. His Adam’s apple bobbed when he watched her laughing, the dusting of pale brown hair moving like wheat stalks.

That head tilt, that laugh, that hand slipping easily down a muscled arm: I couldn’t do it, couldn’t quite understand it. When I tried, the laugh came out broken, the hand too firm on the arm, the head thrown back so fiercely that I could hear my own neck crick. It was a girl thing. I’d watched it right through high school but even now, at twenty, I still couldn’t understand it. It looked like a performance, all of it—the hair flicking, the gathering in giggling groups, the coded language. But I’d somehow missed the rehearsal notes.

In high school, I once watched Sylvie Fagan standing in a group of boys, listening, laughing, smoothing her legs together. As she listened, she rubbed one newly shaven calf against the other. She looked like an elegant flamingo. When I tried it the next day, I lost my balance and tottered sideways, cheeks flaming red, my audience of boys doubling over with laughter. Also, I talked too much, tried to match the boys with their jokes and stupidity, tried to outdo them.

In that apartment, with Penny in the kitchen and me in the living room, I balanced on the arm of a sofa, kicking my green boots out in front of me. Three girls danced in front of a faux fireplace while an American man shouted encouragement. They followed each other seamlessly: hand up, hip jut, click and turn. Hips swaying, shoulders shimmying. Those girls. Their hips were narrow in a way mine never could be, their hair long and shining. They seemed like girls from hair product advertisements. I kicked the pointed toes of my boots and pretended not to notice, not to care. The dancing was smooth, the shimmying mesmerising. But if I watched, if I gazed at the dancing trio, I would be—what? Not a girl? A man? I couldn’t understand what I was. If I didn’t want to dance like the dancing girls, shimmying for the shouting, cheering American, what sort of girl was I?

Fury

Fury